Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD): A Fake Disease They Made Up To Erase Victims.

- Dick Gariepy

- Sep 11

- 22 min read

Dick Gariepy | Big Thinky Ouchey

No, i don't haver BPD. You see its not me who is sick, its everyone else. I don't have emotional regulation issues, you have acute sensitivity to annoyance disorder that causes you to experience inappropriate frustration and insensitivity to the justified emotional outbursts of others, reacting to your poor treatment and abuse. There is no cure for it, but luckily with medication and sensitivity training therapy you may live in somewhat normal life.

Borderline Personality Disorder - The Diagnosis You Weren’t Told You Had.

I found the diagnosis the way people find mold, quietly, in the margins. A single word buried in a chart note, tucked between vitals and boilerplate. The room did not change, but the world did. Clinicians who once treated arguments as arguments began treating them as “affect.” Calm descriptions of risk read as “instability.” A police call that should have meant safety became a welfare check with a side of suspicion once the label circulated through the usual channels of gossip and “care coordination.” Evidence lost weight; tone gained charges. I had been recoded.

Here is the blunt version. Borderline Personality Disorder functions as an administrative alias for trauma-shaped behaviour. Systems discount testimony; that credibility deficit breeds isolation; isolation matures into a moral exile that feels like volatility because human beings escalate when unheard. Philosophers call the first move epistemic injustice and the aftermath ethical loneliness—the abandonment that follows harm when institutions refuse uptake (Fricker, 2007; Stauffer, 2015). Clinicians then read the protest behaviours of the abandoned as “borderline,” while the engine running underneath remains trauma: hypervigilance, dissociation, attachment disruption, and the long tail of threat physiology (Herman, 1992/2015; Cloitre et al., 2014).

The aim of this essay is precise. Retire the costume. Replace the personality verdict with trauma-grounded formulations, PTSD and complex PTSD, paired with justice-first practice. Treat the wound; stop litigating the character of the wounded. If that sounds severe, it is. Severity is what you use when a euphemism starts passing for medicine (Fricker, 2007; Stauffer, 2015; Herman, 1992/2015; Cloitre et al., 2014).

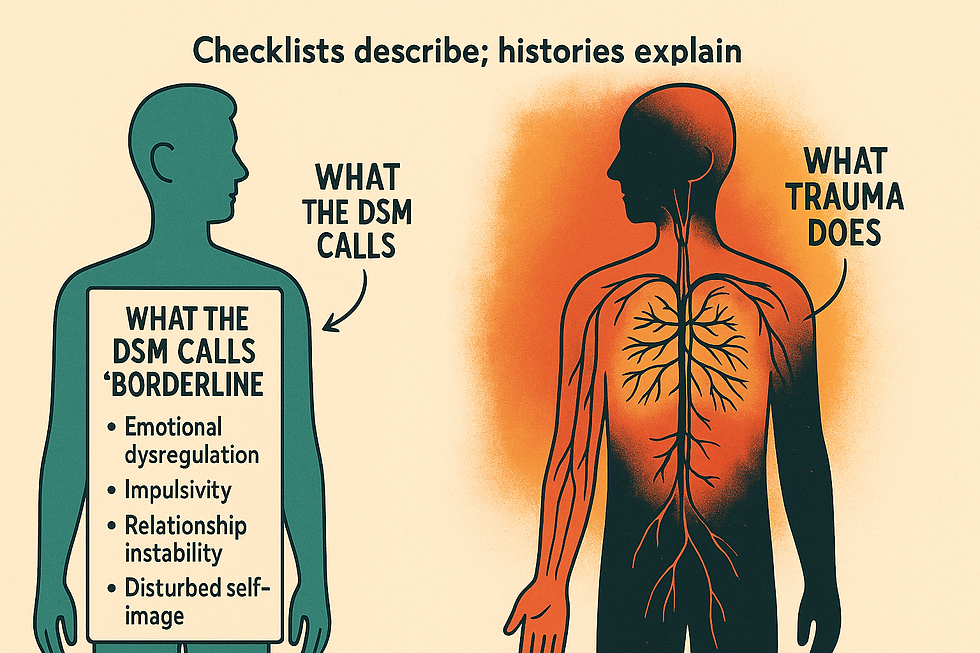

What the DSM Calls “Borderline” vs. What Trauma Does.

The DSM-5-TR criteria for “borderline” compress cleanly into four functional clusters (American Psychiatric Association, 2022):

Affect regulation: Marked mood reactivity, chronic emptiness, and hard-to-govern anger.

Relational volatility: Frantic efforts to prevent abandonment and rapid pivots between idealization and devaluation.

Self-state instability: Identity disturbance and stress-linked paranoia or dissociation.

Impulsivity/self-harm: Risky, short-horizon behaviors and recurrent self-injury or suicidal gestures.

Trauma science already explains these patterns. Hypervigilance amplifies arousal and produces quick mood swings; shame floods and physiological threat cycles empty out subjective life until “numb” becomes a baseline; anger functions as perimeter defense when safety feels provisional (Herman, 2015; van der Kolk, 2014). Attachment disruption trains the nervous system to anticipate loss, so closeness triggers alarm and distance triggers pursuit, an elegant recipe for relational whiplash (Ford & Courtois, 2014). Dissociation and stress-paranoia reflect the mind’s fallback when threat saturates sense-making; identity diffusion follows when survival has required constant self-editing (Herman, 2015; Ford & Courtois, 2014).

The overlaps with PTSD and ICD-11 complex PTSD are structural, not incidental. Re-experiencing and persistent threat appraisal map to affective lability and anger. Disturbances in Self-Organization, affect dysregulation, negative self-concept, and relational impairment, trace directly onto the DSM cluster set above (Cloitre et al., 2014). Avoidance in PTSD has a behavioural twin in the short horizon coping that gets labeled “impulsivity.” Self-harm often operates as down regulation or communication under conditions where testimony fails to move helpers (Herman, 2015; van der Kolk, 2014).

Empirically, comorbidity rates between BPD and PTSD run high, and trauma exposure is the rule rather than the exception among those assigned the label; biological markers remain nonspecific and track arousal systems more than invented traits (Ford & Courtois, 2014; Cloitre et al., 2014; Herman, 2015). The picture that emerges is straightforward: the DSM description reads like a trauma phenotype viewed through an administrative lens.

The Social Construction of “Borderline”.

Diagnoses do cultural work. They organize attention, allocate resources, and script expectations. Some diagnoses also shape the very people they name. Ian Hacking calls these looping kinds: classifications that act on human beings who then adjust to the classification, which in turn adjusts to them (Hacking, 1995, 1999). “Borderline” behaves like a looping kind. The label creates a climate of interpretation, what clinicians notice, how they chart it, which doors open—and that climate feeds back into the next encounter.

Institutions run on codes. Clinics need categories to bill, to triage, to manage risk, and to sort high-friction cases into predictable lanes. Repeated use stabilizes a category; forms, training modules, and handoffs sediment around it. The result resembles discovery but follows the logic of workflow. Michel Foucault mapped this long arc: classificatory power produces subjects who fit the grid laid over them (Foucault, 2006). “Borderline” endures because it helps systems move bodies, justify exclusions, and pre-authorize suspicion.

History leaves fingerprints. The construct drifted from a psychoanalytic borderland case into a practical shorthand for the “difficult patient,” with a distinctly feminized silhouette in many settings (Paris, 2007; Becker, 1963). Staff lore and case conferences prime the lens: volatility becomes personality essence; protest becomes manipulation; ambivalence becomes splitting. This is social learning, not neutral observation. Once the tag appears in a chart, subsequent notes align to it, tone becomes symptom, context fades, and risk language thickens around ordinary distress (Becker, 1963; Paris, 2007).

Validity remains unsettled. Personality disorders promise stable traits; real life delivers state-dependent, context-embedded behaviour that shifts with safety, housing, relationships, and recognition. Reliability improves on paper with checklists; construct validity still trails because the syndrome gathers heterogeneous phenomena under one verdict (Widiger & Trull, 2007). A label that scopes so widely will always seem accurate; it can explain anything because it explains everything.

Label drives perception, and perception drives care. “Borderline” changes how testimony is weighed, how motives are read, and how teams plan. Credibility drops, moralization rises, and options narrow to containment or skills training, even when trauma and structural pressures sit in plain view. The loop closes: classification engineers a presentation that then appears to confirm the classification (Hacking, 1995, 1999; Foucault, 2006).

Epistemic Injustice → Ethical Loneliness → The “Borderline” Presentation.

Epistemic injustice names the first fracture. Testimonial injustice assigns a credibility deficit before the first sentence lands. Accent, chart labels, clothes, posture, diagnosis codes, each loads the scale so that the same report carries less weight in one mouth than another (Fricker, 2007; Carel & Kidd, 2014). Hermeneutical injustice withholds a shared vocabulary for the harm itself. Clinics carry rich language for “compliance” and “risk,” lean language for moral injury, long coercion, and bureaucratic abandonment. Survivors arrive fluent in the latter; institutions answer in the former. The gap produces misreadings that look clinical but function cultural (Fricker, 2007; Kidd, Medina, & Pohlhaus, 2017).

The clinical encounter runs on uptake. Speech acts work only when listeners accept them as the acts they are, reports as reports, refusals as refusals, alarms as alarms (Austin, 1962; Langton, 1993). When uptake fails, speakers do not merely feel ignored; their available actions shrink. People repeat, raise volume, switch channels, add emphasis. In healthcare notes, that adaptive escalation appears as “dysregulation,” “pressured,” “persistently calling,” “boundary testing.” The chart records the countermoves of a person trying to restore uptake (Carel & Kidd, 2014).

Dotson’s account of testimonial smothering explains a second turn of the screw. Speakers learn to self-censor when they expect that full truth will be mishandled or punished. They trim details, pre-dilute claims, or redirect to palatable scripts, trading accuracy for safety (Dotson, 2011, 2014). Smothered testimony then reads thin and unconvincing, which invites more discounting. The loop tightens: credibility deficit → self-protection → apparent evasiveness → deeper deficit. Teams claim “splitting” or “manipulation”; the person is performing risk calculus in a hostile interpretive climate (Dotson, 2011; Carel & Kidd, 2014).

Ethical loneliness names the afterlife of this cycle: abandonment by the very institutions tasked with repair. Harm occurs, a person seeks redress in good faith, and the response arrives as template, shrug, or procedure in lieu of remedy. The result is not only isolation; it is exile from the moral community, exposure without recognition (Stauffer, 2015). Ethical loneliness has a recognizable phenotype: affect that flattens to conserve energy, sudden storms when a narrow opening appears, oscillations between pursuit and retreat in relationships, wary surveillance of helpers, and preemptive self-critique to head off disbelief. The body learns to conserve, the mind learns to scout, and the file learns to moralize (Stauffer, 2015; Fricker, 2007).

This three-part mechanism, disbelief → isolation → protest—converts cleanly to the surface features that get coded as “borderline.” A few canonical mappings make the point:

Fear of abandonment tracks repeated experiences of service withdrawal, gatekeeping, and credibility discounts. When help proves conditional or selectively available, attachment systems calibrate to loss at the door. Pursuit intensifies because loss feels scheduled (Herman, 2015; Ford & Courtois, 2014).

Affective lability and anger follow threat physiology held at a simmer by administrative obstruction and social suspicion. Anger enforces a perimeter when recognition falters; volatility peaks at interfaces where uptake routinely fails (Herman, 2015; van der Kolk, 2014).

Identity instability mirrors prolonged invalidation. Selves stabilize in recognition. Remove uptake, and the self wobbles. Constant self-editing to survive misreadings produces diffusion that then reads as trait rather than as scar (Cloitre et al., 2014; Carel & Kidd, 2014).

Impulsivity and self-harm often function as down-regulation or last-mile communication when ordinary report carries no force. The act speaks because speech failed to register as speech (Linehan, 2015; Ford & Courtois, 2014).

ICD-11’s Disturbances in Self-Organizatio, affect dysregulation, negative self-concept, and relational disturbance, trace exactly this route. Prolonged trauma establishes the physiological baseline; patterned disbelief and moral exclusion shape the relational arena; the observed “borderline” profile emerges as a cPTSD expression under epistemic pressure (Cloitre et al., 2014).

Two micro-scenes clarify the mechanics without romance:

The Report Without Uptake.

A patient calls to say, “I am sleeping two hours a night; my heart is racing; I need a med review.” The portal routes them to a two-week callback. They call again. The file accumulates “multiple calls.” At visit, the clinician opens with “We need to set boundaries around contact.” The patient raises volume to reassert urgency. The note records “labile affect, pressured speech,” and the plan adds “consider BPD traits.” The behavior is a rational amplification in a low-uptake system masquerading as personality essence (Austin, 1962; Carel & Kidd, 2014).

The Partial Story.

A patient omits police misconduct when describing panic because prior disclosures triggered “non-cooperative” flags. They present with fragments. The clinician hears inconsistency. The note reads “unreliable historian, possible splitting.” The person engaged in testimonial smothering to avoid administrative retaliation. The thinness of the account was an index of risk, not deceit (Dotson, 2011; Stauffer, 2015).

Documentation practices harden the loop. Notes convert staff friction into patient ontology with adjectives that travel: “manipulative,” “attention-seeking,” “borderline traits.” Each term performs a small institutional magic trick, turning context into character, and invites the next clinician to see through the same lens. Under pressure, teams escalate risk protocols and de-escalate curiosity. Procedure replaces remedy. People become workflows (Mol, 2002; Carel & Kidd, 2014).

The physiology follows the sociology. Hypervigilance, sleep debt, and autonomic arousal degrade executive control and sharpen startle. In that state, micro-invalidations feel like fresh threat and can precipitate abrupt mood shifts and hard pivots in appraisal, what a checklist calls “lability” or “splitting.” Moral exclusion amplifies this effect; exclusion signals “unsafe,” which recruits survival strategies: scanning, testing, withdrawal, and, at times, dramatic bids for recognition when the quieter bids fail (Herman, 2015; van der Kolk, 2014; Ford & Courtois, 2014).

Moral injury deepens the pattern. When helpers with duty to care respond with disbelief or procedural indifference, the harm crosses from clinical to ethical. People reorganize around that breach: the self carries a negative moral remainder (“I must be the problem”) alongside a vigilant prosecutorial strand (“I must build a case”). Either can look like volatility when filtered through a medical workflow designed for symptom checklists rather than contested narratives (Litz et al., 2009; Stauffer, 2015).

An applied summary keeps the line straight:

Input conditions: prior trauma; repeated credibility deficits; thin institutional language for the person’s actual harm.

Intervening processes: failed uptake; testimonial smothering; administrative delays reframed as “persistence”; moral exclusion.

Outputs observed: abandonment preoccupation; affect storms at interfaces; identity wobble in invalidating spaces; short-horizon coping; self-harm as communication.

Diagnostic translation: codes and case-conference lore gather these outputs under “borderline,” masking the generative pathway (Fricker, 2007; Dotson, 2014; Cloitre et al., 2014; Carel & Kidd, 2014; Stauffer, 2015).

The prescription implied by the mechanism remains simple and will anchor the practical sections that follow. Repair uptake. Treat reports as acts that require acknowledgment, not just logging. Expand the interpretive toolkit. Name moral injury, institutional betrayal, coercive dependence, and administrative exhaustion alongside symptoms. Audit documentation. Replace global character adjectives with functional descriptions tied to triggers and needs. When these conditions shift, the “borderline” profile softens because the engine driving it, disbelief matured into ethical loneliness, loses fuel (Fricker, 2007; Freyd, 2013; Carel & Kidd, 2014; Cloitre et al., 2014; Stauffer, 2015).

The frame holds across settings. Emergency rooms, counseling centers, police interfaces, and benefits offices culture the same pathway with different accents. Where epistemic justice grows, volatility recedes. Where uptake stabilizes, identity consolidates. Where moral presence is restored, the complaint stops masquerading as a personality. The DSM checklist records the weather at the symptom surface; the mechanism above explains the climate (Cloitre et al., 2014; Herman, 2015; Ford & Courtois, 2014).

Evidence Review: Trauma Saturation Behind the BPD Label.

The literature converges on a plain picture: the “borderline” profile clusters where trauma density is highest, and the physiological signatures look like threat systems doing their job under prolonged strain. Cohorts diagnosed with BPD report childhood adversity at striking rates, physical, sexual, and emotional abuse; neglect; chaotic caregiving; and exposure to violence, forming the background against which affect storms, identity wobble, and desperate attachment moves make immediate sense (Zanarini et al., 1997; Herman, 2015; van der Kolk, 2014). Comorbidity with PTSD runs high across studies, frequently at or near the midpoint of samples, and rises with cumulative adversity, medical coercion, and adult victimization (Ford & Courtois, 2014; Cloitre et al., 2014). When investigators separate out trauma load, the so-called borderline features track exposure far better than any putative “personality essence,” with emotion dysregulation operating as the key mediator between past harm and present behavior (Carpenter & Trull, 2013; Ford & Courtois, 2014).

Physiology and neurocognition point in the same direction. Patterns include heightened autonomic arousal, startle potentiation, sleep fragmentation, stress-sensitized amygdala responses, and prefrontal control that tires under load, all hallmarks of trauma adaptation rather than unique signatures of a discrete disorder (van der Kolk, 2014; Ford & Courtois, 2014). Biomarker hunts yield overlap with PTSD and complex trauma rather than clean separations; specificity remains elusive, and endophenotypes fail to cohere (Ford & Courtois, 2014). On the ground, treatments with the strongest evidence, for example, dialectical behaviour therapy’s skills in emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal effectiveness, target processes that trauma saturates, which explains why outcomes improve without proving that a stable personality entity sits underneath (Linehan, 2015; Ford & Courtois, 2014).

ICD-11’s articulation of complex PTSD sharpens the analytic lens. Disturbances in Self-Organization, affect dysregulation, negative self-concept, and relational impairment, map neatly onto what the DSM names “borderline,” while etiological linkage to sustained or repeated trauma preserves causal clarity (Cloitre et al., 2014). When researchers model cPTSD and BPD features side by side, shared variance concentrates around trauma-exposure pathways and regulatory failures rather than trait-like character structure (Cloitre et al., 2014; Ford & Courtois, 2014). This is exactly what a construction built on administrative convenience would look like: a wide net catching the behavioral residue of prolonged threat and invalidation.

What counts as good evidence. Longitudinal or prospective designs that measure trauma exposure with detail, track regulatory processes over time, control for selection effects, and assess outcomes beyond symptom checklists raise the signal and lower the noise (Ford & Courtois, 2014; Herman, 2015). Mixed-methods work that adds narrative and ecological sampling captures the lived mechanics of escalation, withdrawal, and relational pursuit better than clinic-bound snapshots (Herman, 2015). Treatment studies that parse mechanisms, which skills moved which outcomes, outperform symptom-only endpoints when the goal is explanatory traction (Linehan, 2015; Ford & Courtois, 2014).

Where the field hedges. Many datasets rely on retrospective self-report and tertiary-care samples enriched for severity. Publication streams often collapse diverse adversities into single scores, masking pattern differences. Biomarkers remain non-specific, and imaging contrasts rarely survive strict correction once arousal and sleep debt are modeled (Ford & Courtois, 2014; van der Kolk, 2014). These limitations complicate precision; they do not overturn the through-line.

Evidence at a glance—compact synthesis.

Childhood adversity prevalence: large majorities in BPD-diagnosed cohorts; dose, response relations with symptom severity (Zanarini et al., 1997; Herman, 2015).

PTSD/cPTSD comorbidity: frequent and consequential; shared variance rides on threat appraisal and regulation failures (Ford & Courtois, 2014; Cloitre et al., 2014).

Psychophysiology: arousal-system signatures common to trauma; absence of BPD-specific biomarkers (van der Kolk, 2014; Ford & Courtois, 2014).

Mechanisms: emotion dysregulation mediates trauma → “borderline” features (Carpenter & Trull, 2013).

Treatment signal: skills targeting trauma-amplified regulation improve outcomes; utility without ontological proof (Linehan, 2015; Ford & Courtois, 2014).

The arc is consistent across decades. Trauma exposure predicts the profile. Regulatory processes carry the effect. Administrative categories chase the residue. When research honors this chain, the findings line up cleanly (Herman, 2015; Ford & Courtois, 2014; Cloitre et al., 2014; Linehan, 2015; van der Kolk, 2014).

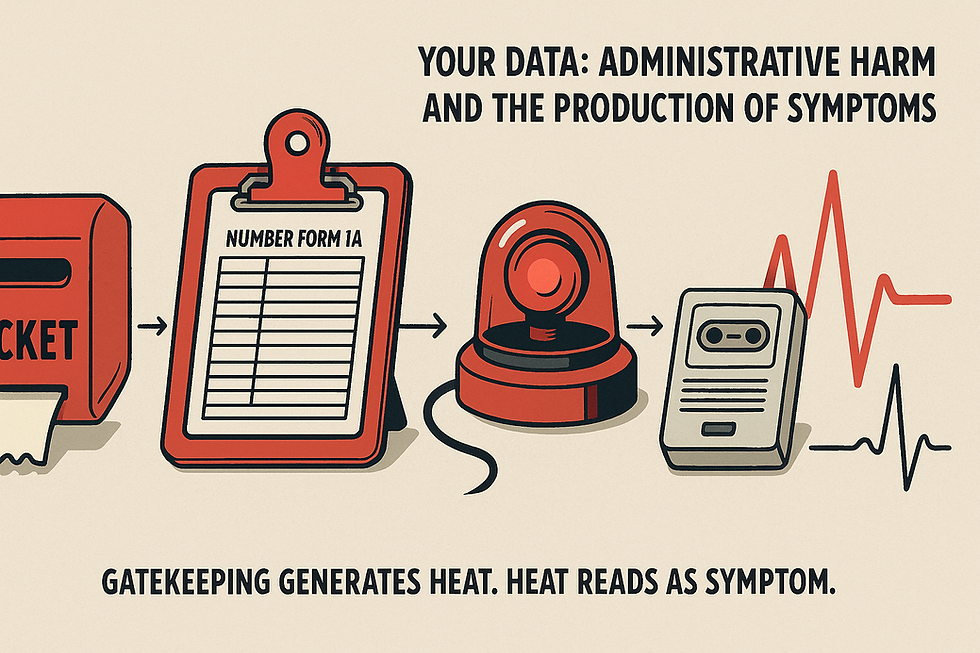

Administrative Harm and the Production of Symptoms.

Two artifacts tell my story in numbers rather than adjectives: (1) my clinical and administrative PDFs from 2021–2025 and (2) the spreadsheet that tracks incidents, handoffs, and responses. I read them like a field log. Certain terms recur with ritual regularity: police contact shows up roughly two dozen times; threat/risk language crosses the page more than fifty times; referrals and re-referrals stack into the thirties; gatekeeping and triage phrasing approaches forty instances; welfare checks appear several times; non-compliance/AMA markers hover around ten; diagnosis tagging, including “borderline”, lands more than fifty times; suicide-risk phrasing crowds the margins with scores of mentions. The tone is neutral, almost antiseptic. The pattern is not.

Here is what happens on the ground. I call with a clear problem, sleep collapse, racing heart, spiraling arousal, and receive a callback window long enough to guarantee deterioration. I call again. The chart now carries “multiple calls.” Intake scripts pivot to boundaries and risk. My nervous system responds to delay and suspicion with vigilance and heat. The next note records “labile affect,” “escalation,” or “persistence.” The following encounter references “borderline traits.” The paperwork narrates a personality; my body narrates a threat response. The two stories diverge in content while aligning in time (Herman, 2015; Ford & Courtois, 2014).

Gatekeeping and referral ping-pong generate the first surge. Uncertainty plus delay strips agency, and agency loss feeds arousal. My sleep shreds. Startle climbs. I press harder for care because the window is closing. The file translates urgency into “boundary testing.” Risk-speak generates the second surge. Monitoring displaces remedy, and surveillance replaces listening. Credibility thins under the weight of forms. Each “threat assessment” adds a degree to the temperature; the physiology follows (Carel & Kidd, 2014; van der Kolk, 2014).

Law-enforcement interfaces add ignition. A welfare check places a uniform between me and help. My heart rate spikes before the door opens. Words come clipped because the stakes just rose. The narrative in the record shifts toward “behavioral volatility.” The mask slips from trauma to personality because the system prefers workflow to causality. I can trace the line: gate, delay, arousal, pursuit, moralization, code. It reads like choreography (van der Kolk, 2014; Hacking, 1999).

I also see the quiet mechanics of epistemic injustice stamped across the pages. My reports arrive with a built-in credibility deficit, and the organization lacks a shared vocabulary for the moral wound at the center of the picture, ethical loneliness, the abandonment that follows harm when institutions refuse uptake (Fricker, 2007; Stauffer, 2015). Intake captures “risk” with precision and “betrayal” with silence. The record treats protest as symptom and procedure as care. Adams and Balfour call this administrative evil, ordinary practices that normalize injury while maintaining professional sheen (Adams & Balfour, 2009).

Read a few neutral lines from my documents and the structure appears:

“Welfare check requested… following up.”

“Advised to go to ED if at risk of suicide… slightly elevated chronic risk.”

“Police currently on scene? No.”

Each phrase performs a small translation. A plea for remedy becomes a note in a surveillance ledger. A request for timely adjustments becomes a safety boilerplate. The signal that matters, the wound and its moral remainder, drops out of frame (Carel & Kidd, 2014; Fricker, 2007).

The category work then closes the loop. Once “borderline” lands in a chart, subsequent descriptions align to it. Tone becomes trait. Context becomes character. Handoffs spread the silhouette through teams. This is Hacking’s looping kind in clinic clothing: the classification reshapes perception and practice, and the reshaped practice then appears to confirm the classification (Hacking, 1999). Meanwhile, my physiology keeps score, sleep debt, hypervigilance, anger as perimeter defense, and short-horizon coping that, on paper, reads as impulsivity (Herman, 2015; Ford & Courtois, 2014).

Here is my clean chain of custody:

Input conditions: long trauma history; credibility discounts at points of entry; administrative vocabulary rich in risk and sparse in moral injury.

Intervening processes: delayed callbacks, referral churn, testimonial downgrades, and police-adjacent touch points that amplify arousal.

Outputs observed within 24–72 hours: sleep collapse, autonomic surge, intensified pursuit of help, relationship blow-throughs at service interfaces.

Diagnostic translation: team lore and checklist convenience gather these outputs under “BPD,” and the code then back-justifies future readings (Fricker, 2007; Stauffer, 2015; Hacking, 1999).

I want the remedy to fit the injury. Restore uptake at the first contact. Treat reports as acts that require acknowledgment, not just logging. Replace global trait language with functional descriptions tied to triggers, conditions, and needs. Address exposures and moral injury alongside skills and safety.

Paperwork builds realities. Better paperwork builds better ones.

The Policy Machinery: Why the Label Survives

Institutions prize categories that move bodies through corridors. “Borderline” earns its keep because it routes work. A code unlocks billing, triggers standardized plans, and satisfies documentation audits. Throughput improves when a chart carries a tidy verdict that justifies surveillance, boundaries, and skills classes. The category functions as infrastructure, rails under the clinic, rather than as a discovery about persons (Bowker & Star, 1999).

Street-level practice runs on scarcity. Front-line staff manage time, risk, and complaint volume with heuristics that ration attention. Under pressure, the shortest path wins: assign the label, invoke the protocol, clear the queue. Discretion narrows to policy-shaped moves that feel like care because they are procedurally correct (Lipsky, 1980). Risk language becomes a shield. “Appears,” “likely,” and “traits” spread liability thin while authorizing containment. The file reads safe; the person reads managed (Adams & Balfour, 2009).

Classification also organizes accountability. Quality metrics track whether forms are complete, whether a risk screen is filed, whether a referral fires. Metrics do not track whether uptake occurred, whether moral injury was named, or whether sleep returned. What gets measured gets repeated. The label prospers because it produces countable events, screens, flags, consults, groups, that satisfy dashboards (Bowker & Star, 1999; Adams & Balfour, 2009).

Care does not appear as a single thing across settings; it is enacted differently at intake, on the ward, and in the EHR. Each site performs the category in a way that stabilizes it. At triage, “borderline” means boundary talk. On the unit, it means observation levels. In the record, it means a billable narrative with tidy causality. Multiplicity does not dilute the label; it fortifies it by making it useful everywhere (Mol, 2002).

This is the quiet engine: a label that standardizes workflow, shields institutions, and feeds metrics will endure. Its persistence signals administrative convenience, practiced daily, and reinforced by policy and payor logic, not empirical necessity about human nature (Lipsky, 1980; Bowker & Star, 1999; Mol, 2002; Adams & Balfour, 2009).

Counterpoints and Rebuttals.

Claim 1: “The BPD construct has treatment utility. DBT works.”

DBT shows that emotion regulation, distress tolerance, interpersonal skills, and mindfulness change outcomes because they target processes that trauma amplifies. A model that improves regulation establishes mechanistic leverage, not personality ontology. When skills training reduces crises and self-harm, the evidence points to a dysregulation loop sensitive to learning and context, features of trauma adaptation rather than fixed character. Mutable targets imply a process diagnosis. (Linehan, 1993/2015; Ford & Courtois, 2014; Carpenter & Trull, 2013.)

Claim 2: “Some presentations look trait-like and persistent.”

Apparent trait stability often reflects chronic exposure to unresolved stressors, ongoing invalidation, and structural barriers that keep the arousal system keyed up. Persistence tracks conditions, housing insecurity, policing interfaces, gatekeeping, not essence. Long arcs of distress resemble sediment: layers of unattended injury, each compacting the last, until behavior looks durable. Remove the drivers, and the profile softens with striking regularity. Chronicity reads as the half-life of unremedied harm. (Cloitre et al., 2014; Ford & Courtois, 2014; Carpenter & Trull, 2013.)

Claim 3: “The label aids communication across teams.”

Teams communicate best when they share functions, triggers, and concrete safety plans. A global character verdict compresses complexity and invites moral inference; a functional brief does the opposite. “Escalates when sleep <4h; de-escalates with same-day med review; avoid police relay; offer written plan at discharge” moves care forward. Function-based language increases precision, reduces bias, and travels cleanly. (Ford & Courtois, 2014; Cloitre et al., 2014.)

Claim 4: “Plenty of cases show no trauma history.”

Absence of documentation does not equal absence of exposure. Under-reporting, testimonial smothering, and hermeneutical gaps hide events that matter; covert and cumulative adversities rarely live in charts. Prospective and mixed-methods work repeatedly uncovers exposure once conditions for uptake improve. Hidden inputs remain inputs. (Herman, 1992/2015; Cloitre et al., 2014; van der Kolk, 2014.)

These replies converge: where mechanisms are modifiable and context explains persistence, a process formulation outperforms a personality verdict.

What Ethical Care Looks Like When You Remove the Costume.

Here is the standard I hold myself to and ask others to meet.

Trauma-first formulation. Begin with exposures, losses, and current structural stressors; write a one-sentence moral injury statement before you touch a checklist. Specify mechanisms: sleep debt → autonomic arousal; police interfaces → threat appraisal; gatekeeping → protest behaviors. Name triggers, buffers, and practical levers (e.g., same-day med review restores sleep; written discharge plans reduce re-escalation). A formulation that traces causes earns trust and guides action (Cloitre et al., 2014; NICE, 2018).

Epistemic justice in the room. Do credibility repair out loud.

“I accept your account as the basis for care.”

“Here is what I think I heard; add or correct.”

Practice co-narration: build shared language for institutional betrayal, moral injury, and coercive dependence so the harm has words that travel across teams (Fricker, 2007; Carel & Kidd, 2014). Avoid hedging that signals disbelief. Ask consent to quote key sentences into the chart; quote them verbatim so the record preserves the claim rather than an interpretation (Fricker, 2007; Stauffer, 2015).

Care pathways that fit cPTSD. Anchor treatment in ICD-11 Disturbances in Self-Organization: affect regulation, self-concept, relationships. Offer skills that down-regulate the body (paced breathing, grounding, sleep restoration), skills that widen choice under load (distress tolerance, impulse control), and skills that stabilize attachment expectations (interpersonal effectiveness). Add trauma-focused modalities when the foundation holds. Build a crisis plan that reduces police relays, provides same-day contact routes, and specifies what de-escalates this nervous system (Cloitre et al., 2014; Linehan, 2015; NICE, 2018).

Documentation that describes functions, not character. Replace verdicts with mechanism-rich sentences.

Instead of: “Manipulative; BPD traits.”

Use: “Escalation after delayed callback; arousal decreased when appointment advanced 48h; requests clarity on follow-up route.”

Instead of: “Fear of abandonment.”

Use: “Marked anxiety after service withdrawal; seeks written plan and confirmed contact person; anxiety lowers when plan provided.”

Chart precipitant → response → effective lever. This format travels cleanly across shifts and disciplines (Carel & Kidd, 2014; NICE, 2018).

An accountability loop that measures what matters. Track time-to-uptake, return-of-sleep within 72 hours, police involvement rate, and the proportion of notes with patient-authored lines. Review monthly with the patient present. Audit the chart for testimonial deficits and hermeneutical gaps: Where did disbelief creep in? Which concepts were missing? Close those gaps and update the formulation in writing (Fricker, 2007; Stauffer, 2015; NICE, 2018).

A working pledge.

I treat reports as actions that require acknowledgment.

I document mechanisms and levers, not personalities.

I co-author the narrative and keep it editable.

Care organized this way replaces theatrical diagnosis with intelligible causality. Volatility softens when uptake stabilizes; identity steadies when recognition returns; safety improves when the plan fits the wound (Cloitre et al., 2014; Carel & Kidd, 2014; NICE, 2018; Stauffer, 2015; Fricker, 2007)

Conclusion, Retire the Verdict, Treat the Wound.

Borderline Personality Disorder performs as a bureaucratic alias for trauma under disbelief, an administrative costume that converts protest into pathology and workflow into ontology. The mechanism has stayed steady across the pages: credibility discounted, meanings withheld, ethical loneliness installed, behaviours read as essence. Trauma explains the profile; policy preserves the label.

The stakes run through every encounter. Accuracy governs whether care tracks causes or chases shadows. Dignity governs whether a person appears as a claimant with a wound or a file with a temperament. Safety governs whether escalation quiets through uptake or intensifies under surveillance. Cost lands in bodies first, sleep debt, autonomic strain, ruptured ties, and in systems next, avoidable crises, police relays, defensive paperwork.

Choose a different architecture. Lead with trauma-grounded formulation. Practice epistemic justice out loud. Build plans that reduce arousal and remove police from the care loop. Chart functions, triggers, and levers; retire global character verdicts. Audit for uptake, not just form completion.

Ethical loneliness turns human beings into paperwork. Justice turns paperwork back into people. Retire the costume. Treat the wound.

Big Thought Thumper -------> Fluent In Foriegn

Inspired by K. Steslow 2010 article 'Metaphors in Our Mouths: The Silencing of the Psychiatric Patient' , this song is about the quiet violence of being forced to translate yourself in order to survive. Not linguistically, existentially. It’s about learning to speak in a dialect that isn’t yours, just to be let in, just to be perceived as coherent. When the cost of being heard is the burial of your native self. Fluent in Foreign is what happens when you stop saying what’s true and start saying what works. It’s what happens when every “I’m fine” buys you a little safety. When you dress your grief in the language of growth because no one wants to hear you bleed, they want to hear you process. It’s about being rewarded for disappearing in plain sight. They called it healing. They called it maturity. But all I did was get good at their grammar. They called me articulate, when all I’d done was gut myself into something that fit their narrative. I became understandable, and in doing so, became unrecognizable to myself. This is not a song about confusion. It’s a song about betrayal, the kind where you do it to yourself because the alternative is silence. The kind where you forget how you used to sound before you learned the words that made them stay.

References

Adams, G. B., & Balfour, D. L. (2009). Unmasking administrative evil (3rd ed.). M.E. Sharpe.

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.).

Austin, J. L. (1962). How to do things with words. Oxford University Press.

Becker, H. S. (1963). Outsiders: Studies in the sociology of deviance. Free Press.

Bowker, G. C., & Star, S. L. (1999). Sorting things out: Classification and its consequences. MIT Press.

Carel, H., & Kidd, I. J. (2014). Epistemic injustice in healthcare: A philosophical analysis. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 17(4), 529–540.

Cloitre, M., Garvert, D. W., Weiss, B., Carlson, E. B., & Bryant, R. A. (2014). Distinguishing PTSD, complex PTSD, and borderline personality disorder: Findings from a community sample with trauma exposure. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123(3), 675–684.

Courtois, C. A., & Ford, J. D. (Eds.). (2014). Treating complex traumatic stress disorders in adults: Scientific foundations and therapeutic models. Guilford Press.

Dotson, K. (2011). Tracking epistemic violence, tracking practices of silencing. Hypatia, 26(2), 236–257.

Dotson, K. (2014). Conceptualizing epistemic oppression. Social Epistemology, 28(2), 115–138.

Foucault, M. (2006). History of madness (J. Murphy & J. Khalfa, Trans.). Routledge. (Original work published 1961)

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford University Press.

Gunderson, J. G. (2008). Borderline personality disorder: A clinical guide (2nd ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Hacking, I. (1995). The looping effects of human kinds. In D. Sperber, D. Premack, & A. J. Premack (Eds.), Causal cognition: A multidisciplinary debate (pp. 351–383). Oxford University Press.

Hacking, I. (1999). The social construction of what? Harvard University Press.

Haslanger, S. (2012). Resisting reality: Social construction and social critique. Oxford University Press.

Herman, J. L. (2015). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence—from domestic abuse to political terror (Rev. ed.). Basic Books. (Original work published 1992)

Kidd, I. J., Medina, J., & Pohlhaus, G., Jr. (Eds.). (2017). The Routledge handbook of epistemic injustice. Routledge.

Langton, R. (1993). Speech acts and unspeakable acts. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 22(4), 293–330.

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press.

Linehan, M. M. (2015). DBT skills training manual (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. Russell Sage Foundation.

Litz, B. T., Stein, N., Delaney, E., Lebowitz, L., Nash, W. P., Silva, C., & Maguen, S. (2009). Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(8), 695–706.

Mol, A. (2002). The body multiple: Ontology in medical practice. Duke University Press.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2018). Post-traumatic stress disorder (NICE Guideline NG116).

Smith, C. P., & Freyd, J. J. (2013). Dangerous safe havens: Institutional betrayal exacerbates sexual trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(1), 119–124.

Stauffer, J. (2015). Ethical loneliness: The injustice of not being heard. Columbia University Press.

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Widiger, T. A., & Trull, T. J. (2007). Plate tectonics in the classification of personality disorder: Shifting to a dimensional model. American Psychologist, 62(2), 71–83.

World Health Organization. (2022). International classification of diseases 11th revision (ICD-11): Complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) diagnostic guidelines.

Zanarini, M. C., Frankenburg, F. R., Dubo, E. D., Sickel, A. E., Trikha, A., Levin, A., & Reynolds, V. (1998). Axis I comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155(12), 1733–1739.

Comments